When organizations talk about deploying AI agents, the conversation often defaults to discussing models, prompts, or chatbot capabilities. But that misses the harder question: how do you design a system where AI agents coordinate, share context, enforce governance, and work across enterprise platforms without breaking or becoming ungovernable?

Agentic architecture is the name of the structural framework that determines this. It's less about any individual agent's intelligence and more about the design of the whole system.

Without explicit architecture, it may lead to inconsistent results across interactions, or make unauditable changes to production systems.

What agentic architecture really means

Agentic architecture is the system design for how AI agents perceive, reason, coordinate, and act. It's the structure of the whole agentic system: layers, protocols, memory, control, and integration.

A customer service chatbot that retrieves an order status is performing a simple tool call. This is essentially a function.

But an agentic system that detects order issue patterns across thousands of interactions, coordinates with inventory and logistics agents, proposes resolution workflows, logs all actions with timestamps and rationale, and escalates to humans when thresholds are crossed is doing something quite different.

This is a coordinated system with explicit orchestration, shared context, multi-agent workflows, and embedded governance. And it doesn’t happen automatically because you connected an LLM to some APIs. The system is architected.

This architecture determines whether the system behaves predictably at scale or becomes a source of operational risk.

Five questions to answer when designing an agentic architecture

Any agentic system, whether a single-use assistant or an enterprise-wide platform, should answer five fundamental architectural questions. These help you avoid “spinning up an agent to see what happens” so you can understand if a design will actually hold up under real conditions.

1. What defines an agent in this system?

In practice, an agent is a software entity with a goal, capabilities (tools and APIs), autonomous action selection based on observations, and access to context and state. It's typically powered by a large language model or other machine learning models, but the agent abstraction includes more than just the model.

You must define agent boundaries, responsibilities, and contracts. You can't just connect a chatbot to an LLM and see what happens. Each agent needs:

-

explicit scope (what it's responsible for)

-

interfaces (how it communicates with other agents and systems)

-

constraints (what it's not allowed to do)

2. How are agents composed and coordinated?

Coordination determines where control and accountability live. The architecture dictates whether you have a central orchestrator coordinating task routing and delegation to other agents, a more decentralized peer-to-peer pattern where agents interact directly with weaker central control, or a hybrid model.

Each pattern has tradeoffs. Central orchestration makes governance and observability easier but can become a bottleneck. Decentralized coordination offers flexibility and local specialization but makes it harder to audit cross-agent workflows or prevent emergent behavior you didn't design for.

3. Where does state and context live?

For an AI system to handle complex tasks that involve multiple steps (like processing a request over time), a simple, one-time command (a "stateless call") isn't enough. The AI "agent" needs a dedicated place to store and retrieve its memory and context. This memory includes the history of its conversation, the user's preferences, and the information gathered from its previous actions.

Memory and state management are design decisions with real tradeoffs. It’s essentially a question of where an AI system “keeps its notes.”

Two fundamental ways agents can remember things are shared memory (centralized) and personal memory (local).

-

Centralized memory is like a shared company database or Google Doc. Every agent reads and writes to the same source of truth. This makes it easier to audit what happened, ensure compliance, and keep everyone aligned. But it can be slower, and if every agent has to constantly check the central system, it creates bottlenecks and tight dependencies.

-

Agent-local memory is more like personal notebooks. Each agent keeps its own short-term memory of what it’s doing. This is faster and gives agents more independence, but it introduces risk. Two agents might remember different versions of the truth, leading to confusion or inconsistent decisions.

Because of their different benefits and drawbacks, most real-world systems take a hybrid approach where central memory stores what has to be correct and traceable, and local memory stores what has to be fast and temporary.

This way, the system stays fast and flexible, without losing control or accountability.

If you don't explicitly design where context lives and how it's shared, agents will either lose track of what they're doing or step on each other in unpredictable ways.

4. How do agents interact with enterprise systems?

Real enterprise value comes from cross-system workflows: an IT ticketing agent that checks ITSM status, queries identity systems for permissions, updates Slack, and logs to compliance systems. That requires standardized connectors, tools, and workflows with explicit triggers, actions, policies, and approvals.

Agents need to handle heterogeneous APIs and schemas, network failures, authentication, rate limits, and partial success scenarios where one system responds but another times out. Therefore, tool and integration architecture is foundational. If your enterprise systems are siloed, poorly documented, or lack APIs, agentic AI will amplify those problems.

5. How is behavior governed and audited at scale?

Governance must be architectural instead of retrofitted. The system has to encode policy constraints, guardrails on tool use, escalation to humans, and audit trails at the orchestration and data layers, not bolted on after agents are in production.

What can this agent change in core systems, under what conditions? How do we know what it did, after the fact? When does a human have to review or approve an action? These translate into technical requirements for policy engines, centralized logs, role-based access, and workflow approvals.

Trying to retrofit governance means re-architecting agent boundaries, data access paths, and logging. It's expensive and fragile.

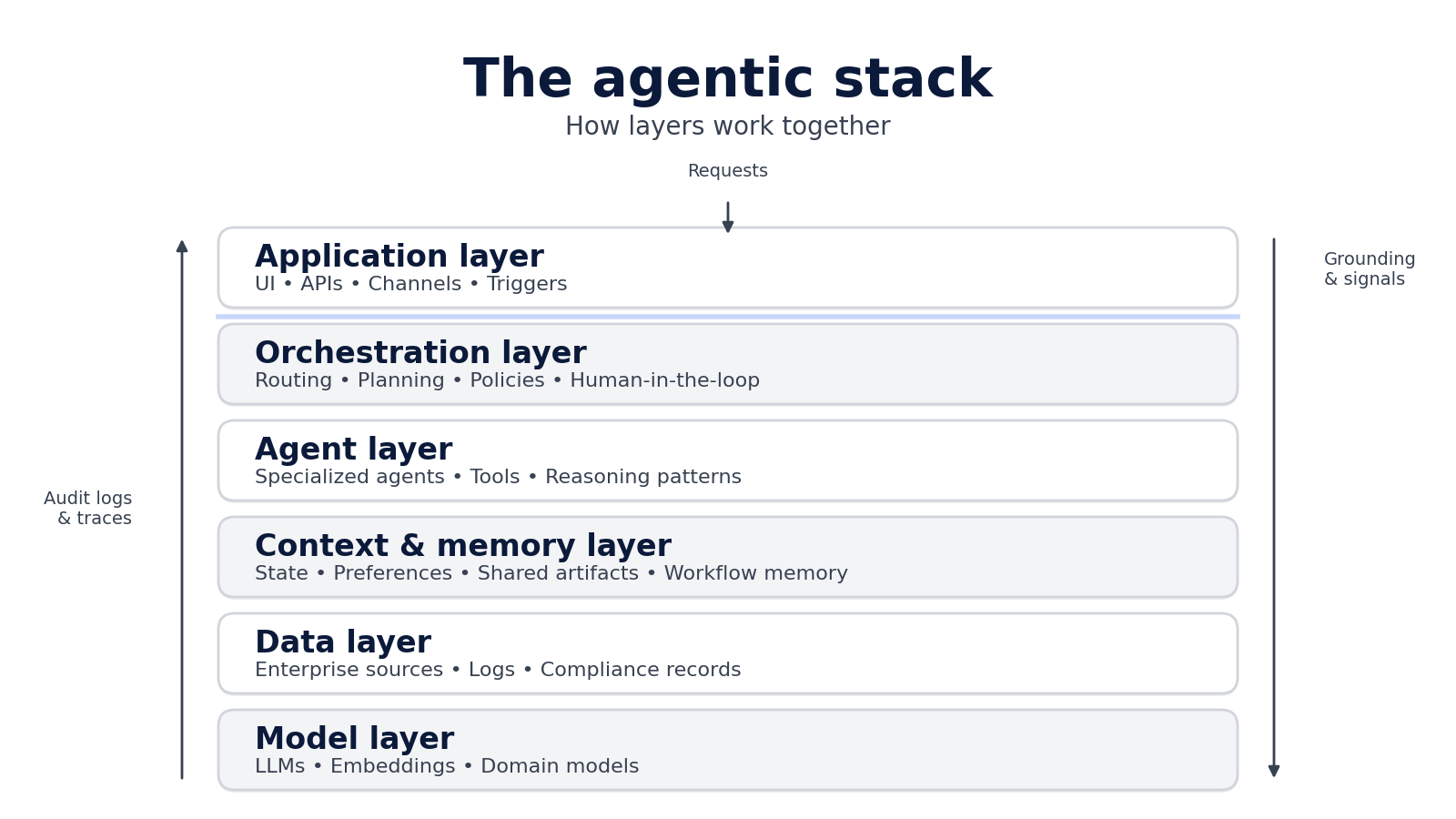

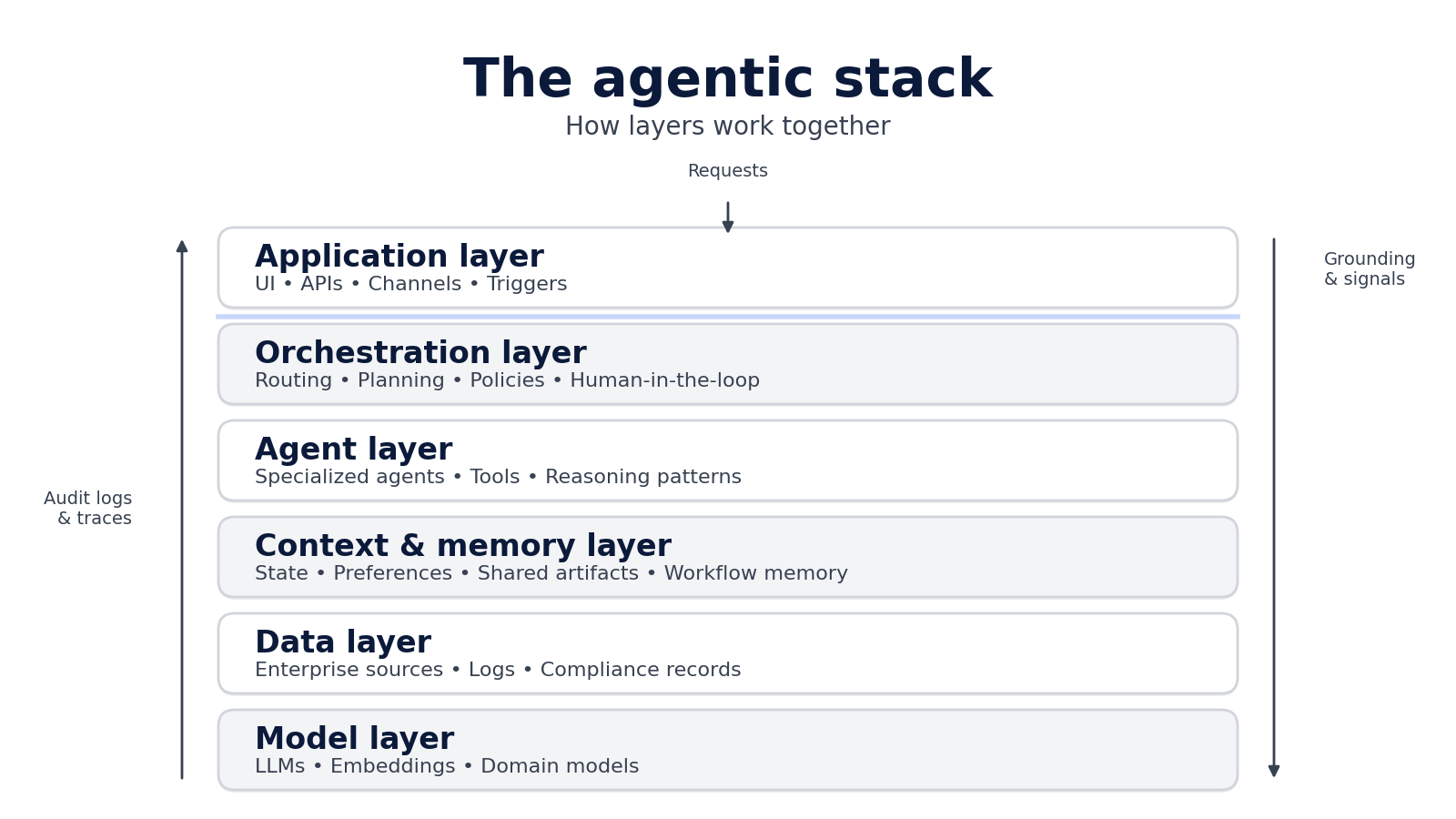

The agentic stack: how layers work together

A common, stable decomposition that surfaces in production systems is the agentic stack as layered architecture. This is how teams organize responsibilities, manage complexity, and enforce separation of concerns when building systems where multiple agents coordinate under governance.

Application layer

The application layer is where humans or other systems interact with agentic capabilities. That includes user interfaces, chat channels, APIs, and workflow triggers. This layer handles authentication, basic user experience, and channel-specific behaviors like formatting responses for Slack versus a web app versus an API consumer.

Orchestration layer

The orchestration layer routes work, decomposes goals, coordinates multiple agents, and manages workflow lifecycle. It often hosts the planner or task decomposer, the policy engine, human-in-the-loop hooks, and retry and compensation logic when something fails partway through a multi-step process.

This is where governance gets enforced. Escalation rules, approval workflows, and cross-agent coordination all happen at the orchestration layer. Without it, you're relying on individual agents to self-coordinate, which doesn't scale and makes auditing nearly impossible.

Agent layer

The agent layer contains specialized agents with domain focus: IT troubleshooting, HR onboarding, analytics, content generation. Each agent has tooling (APIs, retrieval mechanisms, scripts) and local reasoning patterns (prompting strategies, chain-of-thought logic, tool-calling sequences).

Context and memory layer

The context and memory layer maintains state across interactions and workflows, and not just within a single LLM call. This includes conversation history, user and organizational preferences, shared artifacts like plans or intermediate results, and long-running workflow state.

Persistent, scoped memory is a hard architectural problem. Some platforms provide this as infrastructure. For example, Agent Studio offers server-side memory across conversation, user, and agent scopes, integrated with personalization signals. This approach means teams avoid building custom data stores while maintaining context consistency across sessions and agents.

Data layer

The data layer includes enterprise data sources, feature stores, operational logs, and compliance records. It feeds agents with domain context and captures all actions for governance and analytics. Data access must be governed: who can read what, under what conditions, with what masking or anonymization.

Model layer

The model layer contains LLMs and other machine learning models that can include general-purpose LLMs, domain-specific models for classification or scoring, and retrieval or embedding models. Many teams prefer to use bring-your-own-LLM approaches to avoid vendor lock-in and optimize for specific use cases, cost structures, or regulatory requirements.

Together, these layers turn agents from isolated AI tools into governed, production-grade systems.

Each layer plays a role in making behavior predictable, auditable, and scalable. Agents consume data and context, take actions, and update shared state through structured pathways. As a result, memory, coordination, and governance are designed into the system from the start, rather than emerging accidentally from prompts or ad hoc workflows.

Architectural patterns and their tradeoffs

Architectural patterns aren't about picking the "best" design, but more about matching structure to constraints: governance needs, integration complexity, team maturity, and acceptable risk. There's no universal right answer, only explicit tradeoffs.

Centralized vs. decentralized orchestration

Centralized orchestration means one component manages workflow: easier governance, debugging, and consistent policies, but potential bottleneck and single point of failure. Decentralized or peer-to-peer coordination offers flexibility and local specialization but introduces coordination bugs and governance drift.

When to choose one over the other:

-

centralized for regulated industries like finance and healthcare where auditability is non-negotiable.

-

decentralized for rapid experimentation or loosely coupled domains where agents operate mostly independently and failure in one domain doesn't cascade.

Agent granularity (coarse-grained vs. fine-grained)

-

Coarse-grained "super-agents" simplify coordination but prompts become unmanageable and composability suffers.

-

Fine-grained specialized agents offer better modularity but orchestration overhead and context fragmentation increase.

Most stable systems end up relying on domain-specialized agents with clear contracts, for instance "IT troubleshooting agent," "HR policy agent," or "inventory check agent." This is a “not too broad, not too narrow” approach.

State management strategy

Centralized context stores are easier to audit and share but introduce latency and coupling risks. Agent-local memory offers better performance and autonomy but risks inconsistent state views when multiple agents need coordinated understanding. Hybrid patterns work well in practice: centralized for audit and compliance-critical data, local caches for performance-sensitive lookups.

Tool use and permissions

-

Over-permissive tools create unexpected side effects and security risks, for example an agent with write access to a production database can delete data.

-

But over-constrained tools make agents brittle: they can't complete tasks, leading to poor user experience.

The principle of least privilege combined with explicit approval workflows for high-impact actions balances these two paths. And emerging standards like Model Context Protocol (MCP) help teams define scoped, auditable tool access.

For example, Algolia's MCP Server exposes search, analytics, and configuration actions to agents with built-in permissions, rate limiting, and logging. This demonstrates how to control tool use without custom glue code: the server enforces what agents can read, write, and modify at the API level.

Architecture is about encoding tradeoffs explicitly: governance versus flexibility, performance versus consistency, autonomy versus control. The right pattern depends on organizational risk tolerance and operational maturity, not abstract preference.

Retrieval and grounding: how agents access enterprise knowledge

For enterprise and business use cases like customer support, ecommerce, compliance, and operations, answers must be grounded in current, accurate data. This is where retrieval and grounding layers become architecturally critical.

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) is the pattern where agents query external knowledge sources (indexed documents, databases, APIs) before generating responses. This ties outputs to actual evidence.

The agent doesn't just rely on training data or memorized patterns. It fetches real information and uses that to construct answers.

This retrieval layer has its own set of architectural requirements:

-

Performance: sub-second latency at the search layer, so retrieval doesn't bottleneck multi-step agent workflows.

-

Relevance: semantic and structured search with business-aware ranking, not just keyword matching or raw embeddings.

-

Freshness: indices must reflect current state, whether product catalogs, policy documents, or system data.

-

Governance: retrieval must respect access controls, user permissions, and data masking rules.

What "business-aware retrieval" means

Agents in real business use cases must be able to retrieve information that is current, structured, compliant with business rules, and ranked according to real priorities. In other words, they must be capable of “business-aware retrieval”.

Traditional retrieval pipelines like vanilla RAG rely mainly on vector search, which doesn’t understand business rules like compliance status, inventory, pricing, availability, permissions, or priorities.

For example, a vector-only retrieval system might recommend a product that matches the description perfectly, but is out of stock or not a product the merchandising team wants to promote. Or it might surface a policy document that is semantically related to a question an employee asks, but the document is outdated, unapproved, or restricted to a different team

So while the result is technically relevant, it’s not actually relevant operationally. Therefore, we would say that the retrieval isn’t business-aware. With business-aware retrieval, relevance has to be defined by both meaning and business constraints, like:

-

What data is allowed to be shown (permissions, compliance, region)

-

What data is valid right now (in-stock status, current pricing, approved content)

-

What data should be prioritized (high-margin products, recent updates, high-performing items)

To make this possible, two things must work together.

First, you need hybrid retrieval. Hybrid retrieval combines traditional keyword search with semantic vector search into a single retrieval engine, like Algolia’s NeuralSearch, making retrieval more accurate, structured, and reliable than vector-only approaches.

Second, retrieval needs business logic baked into it, like:

-

Indexing business signals like price, inventory, margin, freshness, approval status, or personalization data

-

Applying hard constraints through filters (e.g., only in-stock items, only authorized documents)

-

Applying soft priorities through ranking rules (e.g., boost higher-margin products, prefer newer content, favor enterprise-approved answers)

Together, this gives you the business-aware retrieval foundation for production-grade, business-aware agents.

Common agentic architecture issues and how to fix them

The following are issues teams frequently encounter when agentic systems leave the demo environment and hit production complexity: concurrent users, partial failures, policy conflicts, and integration at scale.

Context confusion and state drift

Multiple agents writing to a shared state without clear ownership or schema leads to misaligned actions.

One agent closes a support ticket. Another agent, working from stale context, reopens it. The user gets contradictory updates. The audit log shows conflicting decisions with no clear resolution path.

The architectural fix: explicit state ownership, versioned schemas, and centralized context management.

-

Define which agent is authoritative for which data.

-

Use schema evolution patterns so context updates don't break agents that depend on older structures.

-

Centralize audit logs so you can trace state changes back to agent decisions.

Hidden coupling via prompts

Teams encode contracts implicitly in prompts: "agent A expects agent B to return JSON with field X." But this is essentially an assumption. Any prompt change to agent B breaks agent A in subtle, hard-to-debug ways. The system works until someone optimizes a prompt for clarity and accidentally removes a field another agent depends on.

The architectural fix: treat agent interfaces like APIs. Use schemas, versioning, and contract testing. If agent A depends on data from agent B, that dependency should be explicit, typed, and tested. Changes to interfaces should trigger integration tests that catch breakage before deployment.

Tooling as an afterthought

Agents depend on slow, flaky tools that were not designed for interactive workloads. The system "works in demo" with mocked data or single-threaded execution. It fails under real concurrency, timeouts, and rate limits. The demo uses a tool that responds in 50ms. Production uses the same tool, which times out after 30 seconds when the database is under load.

The architectural fix: treat tools as first-class components.

-

Design them for the latency, throughput, and concurrency requirements of agent workloads.

-

Build in retries, idempotency, and graceful degradation.

-

Load-test tools before agents depend on them in production.

No explicit error and exception handling

There's no standardized way for agents to represent failure: timeouts, partial results, policy denials. Results in silent failures (agent gives up without telling anyone), hallucinated "success" (LLM generates plausible-sounding confirmation for an action that didn't complete), or nonsensical user-facing errors ("Sorry, I couldn't process your request" with no actionable detail).

The architectural fix: error taxonomy and explicit exception paths in orchestration.

-

Define error types (transient failures, policy denials, data unavailable, tool timeout).

-

Build fallback strategies (retry with backoff, escalate to human, provide partial result).

-

Surface errors to users in ways that preserve trust.

Governance bolted on late

Audit trails, approvals, and access controls added after agents are in production means fragmented policies (different agents follow different rules), inconsistent behavior (sometimes humans are asked to approve, sometimes not), regulatory gaps (no audit trail for certain actions), and expensive retrofits (re-architecting to add governance after the fact costs more than building it in).

The architectural fix: governance as day-one design.

-

Policy engines, approval workflows, and audit logs embedded in orchestration and data layers are baked in from the start.

-

Every tool invocation, every state change, every decision gets logged with enough context to reconstruct what happened and why.

Remember that architecture is what prevents "works in the demo" from becoming "breaks in production."

Practical implications for enterprise decision-makers

Agentic architecture shapes investment decisions, team structure, vendor strategy, and risk. The architectural choices you make (or don't make explicitly) translate directly into organizational and operational realities.

Autonomy is an architectural (and business) decision

How much the system can "do on its own" is determined by tool permissions, orchestration logic (when to stop and ask for help, when to escalate), and governance rules. You're deciding where to place control and accountability: in orchestrators, in policies, in humans, or in combinations of all three. This is a business decision about risk tolerance and operational trust dressed up as a technical one.

Integration and data architecture drive value and risk

Agentic systems are only as useful as the systems they can act on (HR platforms, ITSM, CRM, identity management) and the trustworthiness and accessibility of the data they use.

If your enterprise systems are siloed or poorly documented, agentic AI will amplify those problems and Integration debt will become architectural debt.

Governance must be designed from day one

What can this agent change in core systems, under what conditions? How do we know what it did, after the fact? When does a human have to review or approve an action?

These questions translate into technical requirements for policy engines, centralized logs, role-based access control, and workflow approvals.

"We'll add governance later" is an expensive mistake. Retrofitting governance often means re-architecting agent boundaries, data access paths, and logging infrastructure from scratch.

Complexity grows non-linearly

More agents doesn't equal a linear increase in complexity. It can be exponential if interfaces aren't explicit and state ownership is unclear. Since each new agent can potentially interact with every existing agent (and therefore create an N-squared coordination problem), you should limit and standardize agent types.

Favor a small, consistent set of well-designed agent capabilities over scattered, ad-hoc agents that solve point problems but don't compose cleanly.

Much of this comes down to adopting a platforms-based and framework-based standard of thinking. You need a team that understands distributed systems, security, data modeling, and site reliability engineering.

Observability and iteration are continuous needs

Agentic systems are inherently stochastic (LLMs are probabilistic) and evolving (models update, data changes, user expectations shift). Therefore, architecture (and budget) should support:

-

A/B testing of agent behaviors

-

telemetry on outcomes (not just activity logs)

-

cost tracking (token usage adds up fast at scale)

-

quality monitoring (are responses getting better or worse over time?)

Observability for agentic systems includes tracking search and retrieval quality, tool invocation logs, and outcome metrics.

Algolia provides analytics on query patterns, retrieval relevance, and agent performance to help teams tune behavior over time.

Keep in mind this is one layer of the observability stack. Teams still need broader telemetry on orchestration, errors, latency, and user satisfaction.

Making agentic architecture real: a grounded example

Let's walk through how the layers, coordination, and governance work in practice.

The scenario: an ecommerce brand's AI shopping assistant that helps users find products and answers questions about orders.

User query and application layer

A user asks: "I need waterproof hiking boots under $150, and I'm worried my last order hasn't shipped yet." The application layer (chat UI) authenticates the user and passes the query to orchestration.

Orchestration layer decomposes goals

-

The orchestrator parses the query and identifies two sub-tasks: product search with filtering and recommendations, and order status check.

-

It delegates to specialized agents: Product Discovery Agent and Order Management Agent.

-

It applies policies: the user has read-only access to their own order data, and product recommendations must respect inventory and pricing constraints.

Agents execute with tools and retrieval

-

The Product Discovery Agent uses a retrieval layer to query the product catalog.

-

It combines semantic understanding ("waterproof hiking boots") with structured filters (price under $150, in-stock, user's size preference from profile).

-

It retrieves the top five options ranked by relevance and business signals: popularity, margin, return rate.

-

It constructs context for the LLM: retrieved products plus user history.

-

The LLM generates a conversational response: "Here are three waterproof hiking boots under $150 that match your past preferences..."

-

The Order Management Agent calls the order API to fetch the user's recent orders.

-

It checks shipping status and detects the order is delayed.

-

It generates a response: "Your order #12345 is delayed by 2 days due to a carrier issue. Would you like me to escalate to customer service?"

Memory layer persists context

-

The conversation context (user's product search, order inquiry) is saved for continuity.

-

User preferences (size, brand affinity) are updated in the memory layer.

-

The agents record actions taken (products retrieved, order queried) for audit purposes.

Orchestration synthesizes and governs

-

The orchestrator combines agent responses into a coherent reply.

-

It enforces governance, escalating order changes to humans but handling status checks.

-

All actions (retrieval, API calls, LLM prompts/responses, user interaction) are logged for full traceability.

This is how a coordinated agentic system would work in practice for ecommerce or fashion, and how and why it goes beyond just a basic chatbot.

A checklist before building or buying agents

Whether you're evaluating platforms, frameworks, or building in-house, these questions surface architectural maturity. If a vendor or framework can't answer them clearly, the architecture likely isn't production-ready. Demos are starting points. These questions test depth.

Architecture and design:

-

How are agents defined and coordinated?

-

Is there a central orchestrator, decentralized peer-to-peer, or hybrid?

-

Where does state and context live? Is it centralized, agent-local, or persistent across sessions?

-

How is behavior governed? Are policies, approvals, and guardrails built into the architecture or bolted on afterward?

Integration and data:

-

What systems can agents read from and act on?

-

What APIs, connectors, and latency characteristics exist?

-

How is retrieval and grounding handled?

-

What RAG patterns, relevance mechanisms, freshness guarantees, and access controls are in place?

-

How are tools and permissions managed?

-

Is there least privilege, scoped access, and auditing?

Observability and operations:

-

How do you monitor agent behavior?

-

What logs, metrics, tracing, and cost tracking exist?

-

What happens when something goes wrong?

-

How are errors handled, retries managed, and escalation paths defined?

-

How do you test changes without breaking workflows?

-

Are there staging environments, rollback mechanisms, and A/B testing capabilities?

Organizational readiness:

-

What skills does your team need? Not just prompt engineering but distributed systems, security, data governance, site reliability engineering.

-

How do you plan for continuous iteration? Agents evolve. Architecture must support tuning and optimization, not just one-time deployment.

Agentic architecture as strategic infrastructure

Agentic architecture is about system design: how autonomous capabilities are structured, coordinated, governed, and integrated. It's not about any single model or agent. Use the five questions provided earlier as a framework to getting started with agentic AI.

Remember, enterprise success depends on treating agentic systems like production infrastructure. That means explicit governance, robust error handling, continuous observability, and organizational alignment. Sound architecture leads to success in production and scale.

As AI capabilities mature, the architecture will differentiate winners from those stuck in perpetual pilots.

Learn more about how Algolia can help. Sign up today to try Agent Studio to build workflows powered by Algolia’s AI retrieval engine.