It’s Friday evening, and a junior developer at a fictional company, AuroraMart, decides to push what the team has been working on all week. “Just get it over with,” he mumbles, fumbling over the merge button.

In our story, AuroraMart has an ecommerce business with a search integration with Algolia. They’re using an RMP to accept bids on sponsored results that’ll go at the top of the search results.

AuroraMart has just flipped the switch on their new retail media platform (RMP) — a piece of software like Criteo or Zitcha that lets you accept and manage bids for ad space in your app. When installed correctly, software like this can be immensely helpful at enabling brand partnerships and driving extra revenue from search results. But when used naively, problems start popping up immediately.

AuroraMart found themselves in the latter category. Within minutes, toasters were showing up in search results for tomatoes, and random tech accessories were showing up under the garden section. These obstacles made customers less likely to convert even when they had clear intent to buy, and the numbers backed that up: the staff showed up Monday morning to find that conversion metrics tanked across the board over the weekend and their customer support inbox was overflowing with complaints of excessive ads. What happened?

Why their implementation didn’t work

The developers had tried the “bolt-on” solution, just naively injecting the RMP’s outputs into the search results in the frontend. They were getting search results for every query with Algolia, and then in the InstantSearch frontend, they used a transformation function to return the array of sponsored RMP hits first, followed by the results returned by Algolia. This seemed simple enough, assuming that the RMP returns the right results. Why didn’t this work?

Different motivations: How RMPs work versus search engines

First of all, retail media platforms and search engines have completely different objectives. Our data-driven pitch here at Algolia is that if you connect shoppers to the most relevant search results — the ones they’re most likely looking for — they’ll buy more on average. The RMP’s goal is to make money for the company, not through sales, but through ad buys. It’s not prioritizing what the shopper would most like to see; it’s prioritizing what the advertisers would most like them to see. These priorities overlap almost none of the time, so there’s a big mismatch in the final search results.

No shared search context

Additionally, we send the RMP the search query, but it’s likely not equipped to handle the wide array of filters and facets that Algolia is refining the search results with. The user might be looking for a specific category, price range, brand, or color, and an ad that doesn’t match those facets is very unlikely to be clicked on by the user given the effort they expended in identifying those preferences. The RMP guesses context, leading to headphones in searches for surround sound systems.

Index disconnect

The RMP also doesn’t have easy access to the product index, so if a product is out of stock or doesn’t even exist at all in the product catalog, it’ll get suggested nonetheless. Clicking on those sponsored results not only feels random, but it could actually break the UI, leading to 404 product pages and disappointed hopes for the few shoppers who actually do click on the ads.

Duplicate results

When the RMP actually does suggest a relevant product, another issue pops up: deduplication. The same product might be in the sponsored hits list and in the search results list, appearing twice on the same page. That eliminates the possibility of the user seeing and clicking on a unique product, so conversion will dip proportionately.

The stakes are high

Merchandisers had worked hard to carefully tune their ranking system, but it was completely demolished by arbitrary insertions that were out of their control. Those managing the ad bids weren’t aware of the damage they were doing to the user experience, and in fact they were seeing the revenue pulled in by their team go up (since more ads were being shown), so they kept right on the same track. Engineers wasted half their time for the next two weeks tackling support tickets asking for hardcoded exceptions, like “show this ad, but only in this category”. That transformation function ballooned into a massive file, slowing down page load times and wasting precious time.

They couldn’t just go back though, since they were contractually obligated to show these ads a certain number of times to their audience through their RMP. But the cost of debugging, adding loophole after loophole, frustrating their users… it was adding up.

Solution: don’t roll your own composition

Eventually, the team got together to discuss a solution. They found this page about External Source Groups in Algolia’s docs that outlined the better way to approach integrating with RMPs. Here’s the very first paragraph:

External source groups let you inject specific items into search results based on decisions made by external systems, such as Retail Media Platforms or recommendation engines. Unlike search-based groups (where Algolia selects items matching your criteria), external sources give you precise control over which exact items appear, while Algolia handles placement and optional re-ranking.

That’s exactly what they needed! They decided to let Algolia orchestrate organic and sponsored results through the Composition API.

In Merchandising Studio

The first step was to get the product index and the RMP’s output combined together into one “composition” as Algolia calls it. This can be found in Merchandising Studio, under Compositions. This is the canonical blueprint of how sponsored and organic search results are blended, replacing the frontend transformation function and all of the engineering team’s “little fixes”.

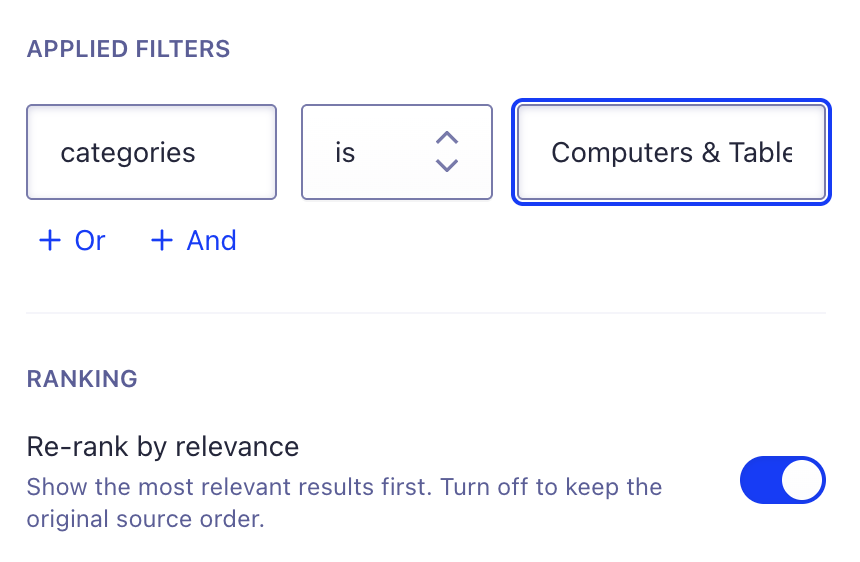

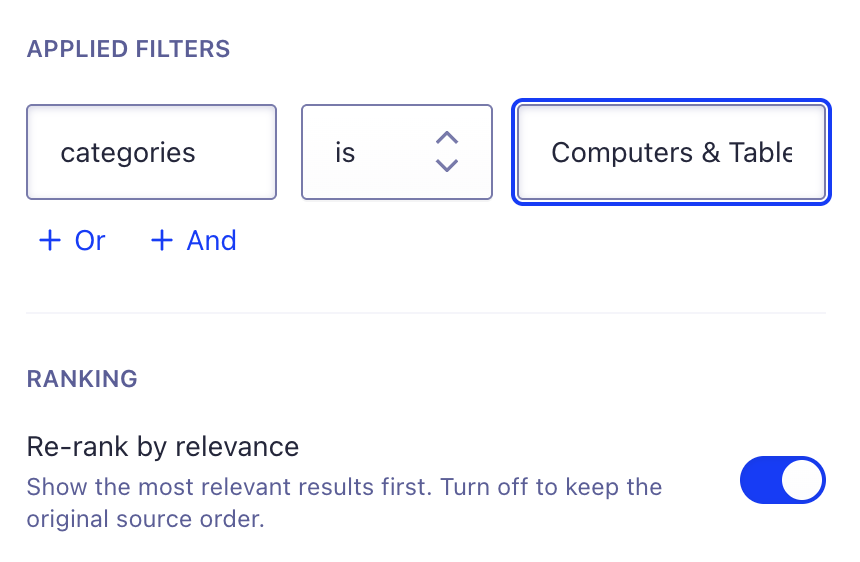

Then under Composition Rules, they could create rules that controlled the conditions under which sponsored placements could appear at all — what collections, queries, contexts, and filters trigger ad spots — and in each scenario they specified how many slots would be reserved for sponsored results. In the composition rule editor, they created a external source group that represented the output of the RMP, which would be injected later.

AuroraMart didn’t just blindly trust the RMP to fully enforce their product constraints, so they added filters directly on the external source group to enforce business rules at the search layer. This made sure that even if the RMP tried to inject something inappropriate, Algolia would drop it if it didn’t match the specific filters. Sponsored products that didn’t respect AuroraMart’s inventory and pricing constraints, for example, just never ended up in the group.

They also let Algolia re-rank the sponsored results, still showing the RMP’s output but changing the order based on their relevance to the given query and context. This is great for almost all cases, but when they were obligated to present the ads in a specific order (perhaps because that was part of a negotiated brand partnership), they could disable this functionality only in very narrow circumstances, avoiding the negative impact it could have on the rest of their product catalog.

Writing the middleware

As far as the code goes, it wasn’t any more complex than copying code from the docs and swapping in environment variables.

First, they defined a fetch function that automatically returned nothing after a certain amount of time:

const fetchWithTimeout = (url, options, timeout) => {

return Promise.race([

fetch(url, options),

new Promise((_, reject) =>

setTimeout(() => reject(new Error('RMP timeout')), timeout)

)

]);

};

This prevents the RMP from holding up the entire searching operation just because it’s not pulling ads fast enough.

Then, we get the sponsored products from our retail media platform however their docs tell us to, except using the fetchWithTimeout function:

let sponsoredItems = [];

try {

// Request sponsored products from RMP

const retailMediaResponse = await fetchWithTimeout(

'<https://rmp.example.com/api/bids>',

{

method: 'POST',

headers: { 'Content-Type': 'application/json' },

body: JSON.stringify({

query,

category,

slots: 5

})

},

RMP_TIMEOUT

);

if (retailMediaResponse.ok) {

sponsoredItems = await retailMediaResponse.json();

// Example response: [

// { objectID: 'camera_123', bid: 2.50 },

// { objectID: 'camera_456', bid: 2.00 }

// ]

}

} catch (error) {

// RMP timeout or error - continue just with organic results

console.warn('RMP unavailable, just showing organic results:', error.message);

}

Then, we transform those sponsored results (if we have them) into a format Algolia wants. Any field Algolia doesn’t understand but we need can be put in as metadata, which will be passed right on through the search engine and into the hits component.

const injectedItems = sponsoredItems.map(item => ({

objectID: item.objectID,

metadata: {

sponsored: true, // Required for regulatory compliance

source: 'retail_media',

bid: item.bid

}

}));

The last step is just to send those injected items to Algolia as part of a search request to the Composition API, like this:

const response = await client.search({

compositionID: 'YOUR_COMPOSITION_ID',

requestBody: {

params: {

query,

hitsPerPage: 20,

// Only include injectedItems if there are sponsored products

...(injectedItems.length > 0 && {

injectedItems: {

retail_media: { // Key must match group name from Merchandising Studio

items: injectedItems

}

}

})

}

}

});

AuroraMart is using InstantSearch for their frontend, so they just redirected InstantSearch’s requests to their new middleware using the techniques in this docs page, and they were done! From there, Algolia takes care of everything else: applying the composition rules, figuring out when to use each composition rule, filtering out inappropriate matches, deduplicating products that appear in both the sponsored and organic hits, and returning a clean set of results to the UI.

Since they added the sponsored flag in the metadata too, they knew when to use the sponsored version of their hits component to comply with regulatory guidelines. This simplified their UI drastically, no longer needing to do any blending logic manually.

How it turned out

AuroraMart saw the results of this better approach everywhere. Sponsored placements became more of an appreciated enhancement and less of a obstacle. They respected the same query, category, and filter context as organic results, so search went back to feeling relevant, integrated, and snappy. Every stakeholder was happier:

Users love the experience

Users could clearly see which placements were sponsored thanks to the consistent badges. The results weren’t random or redundant, so what sponsored ads they did see were likely to be helpful. Sponsored product slots became a way for users to discover new things that were tangential to what they were already looking for, and they didn’t have to wait a substantial amount of time for the whole interface to load.

Merchandisers find it easier

The merchandising team loved the control they got — now they could tell Algolia where to include the sponsored groups from their own UI instead of pestering the developers to make minor tweaks like that. They could enforce quality constraints all by themselves, and the solution scaled to every new campaign and product collection.

Engineers have less to do

Engineers loved the reduced maintenance burden that came from removing bespoke merchandising logic and standardizing it all around a platform somebody else was responsible for. The simple pipeline was easy to wrap their heads around and to train new hires on, so debugging went much faster.

Legal feels safer

The lawyers used to feel like they had to hound everybody else to limit liability, but now they’re resting easy knowing that every sponsored record comes with explicit metadata that marks it as such and is reliably expressed in the frontend UI. They had a clear explanation for where every sponsored ad came from, since the logic was easy to follow and didn’t require looking at code.

The paradigm shift

Before the change, sponsored search was treated like its own thing — a separate widget that was just bolted onto the UI. Every time the merchandisers wanted to adjust something, they had to open another ticket for the engineers, spending precious development time on a hopeless patchwork of edge cases.

After the chat, AuroraMart saw retail media platforms as a smoothly-integrated part of the search process. The RMP manager’s job didn’t require any manual input — just oversight as advertisers bid on space that was already guaranteed to be available when relevant. Algolia handled all the complex logic of deciding how those products appeared inside search, right out of the box.

The paradigm shift is in the separation of responsibilities: the team should control where the sponsored slots show up. The RMP worries about who is placing what ads, and Algolia handles how to place them. Everybody gets to do what they’re best at, and the company’s revenue goes up as a result.

Lessons learned

The main lesson here is that AuroraMart’s failure started way before that Friday evening and the junior developer’s ill-advised push to production. The real failure was baked into the way they were thinking about sponsored results in the first place.

Context drifts, filters are forgotten, edge cases accumulate, and over time these things lead to a RMP’s results not being terribly relevant to the user. And that’s fine! They’re not meant to make the user happy — they’re meant to drive ad revenue for the company. RMPs are not (and were never meant to be) co-equal search engines.

How do you avoid the death spiral of support tickets and ridiculous ads? Treat external systems as sources of objectIDs, and let Algolia orchestrate placement. That’s how you guarantee continued relevance and sensible sponsorships.

AuroraMart’s story isn’t a pitch; it’s a pattern. It's a call for a simpler, higher-ROI mental model: stop rolling your own janky blending logic and instead think in terms of composition pipelines. That’s the difference between a search stack that decays with every campaign and one that stays straightforward as you plug more into it.